[C] - The Critique of Pure Reason

What is meant by this title? Critique is not precisely a criticism, but a critical analysis; Kant is not attacking " pure reason," except, at the end, to show its limitations; rather he hopes to show its possibility, and to exalt it above the impure knowledge which comes to us through the distorting channels of sense. For "pure" reason is to mean knowledge that does not come through our senses, but is independent of all sense experience; knowledge belonging to us by the inherent nature and structure of the mind.

At the very outset, then, Kant flings down a challenge to Locke and the English school: knowledge is not all derived from the senses. Hume thought he had shown that there is no soul, and no science; that our minds are but our ideas in procession and association; and our certainties but probabilities in perpetual danger of violation. These false conclusions, says Kant, are the result of false premises: you assume that all knowledge comes from "separate and distinct" sensations; naturally these cannot give you necessity, or invariable sequences of which you may be forever certain; and naturally you must not expect to "see" your soul, even with the eyes of the internal sense. Let us grant that absolute certainty of knowledge is impossible if all knowledge comes from sensation, from an independent external world which owes us no promise of regularity of behavior. But what if we have knowledge that is independent of sense-experience, knowledge whose truth is certain to us even before experience-a priori? Then absolute truth, and absolute science, would become possible, would it not? Is there such absolute knowledge? This is the problem of the first Critique. "My question is, what we can hope to achieve with reason, when all the material and assistance of experience are taken away." The Critique becomes a detailed biology of thought, an examination of the origin and evolution of concepts, an analysis of the inherited structure of the mind. This, as Kant believes, is the entire problem of metaphysics. "In this book I have chiefly aimed at completeness; and I venture to maintain that there ought not to be one single metaphysical problem that has not been solved here, or to the solution of which the key at least has not here been supplied." Exegi monumentum aere perennius! With such egotism nature spurs us on to creation.

The Critique comes to the point at once. "Experience is by no means the only field to which our understanding can be confined. Experience tells us what is, but not that it must be necessarily what it is and not otherwise. It therefore never gives us any really general truths; and our reason, which is particularly anxious for that class of knowledge, if roused by it rather than satisfied. General truths, which at the same time bear the character of an inward necessity, must be independent of experience,-clear and certain in themselves." That is to say, they must be true no matter what our later experience may be; true even before experience; true a priori. "How far we can advance independently of all experience, in a priori knowledge, is shown by the brilliant example of mathematics." Mathematical knowledge is necessary and certain; we cannot conceive of future experience violating it. We may believe that the sun will "rise" in the west to-morrow, or that some day, in some conceivable asbestos world, fire will not burn stick; but we cannot for the life of us believe that two times two will ever make anything else than four. Such truths are true before experience; they do not depend on experience past, present, or to come. Therefore they are absolute and necessary truths; it is inconceivable that they should ever become untrue. But whence do we get this character of absoluteness and necessity? Not from experience; for experience gives us nothing but separate sensations and events, which may alter their sequence in the future. These truths derive their necessary character from the inherent structure of our minds, from the natural and inevitable manner in which our minds must operate. For the mind of man (and here at last is the great thesis of Kant) is not passive wax upon which experience and sensation write their absolute and yet whimsical will; nor is it a mere abstract name for the series or group of mental states; it is an active organ which moulds and coordinates sensations into ideas, an organ which transforms the chaotic multiplicity of experience into the ordered unity of thought.*

*Radical empiricism" (James, Dewey, etc.) enters the controversy at this point, and argues, against both Hume and Kant, that experience gives u» relations and sequences as well as sensationi and events.

But how?

1. - Transcendental Esthetic

The effort to answer this question, to study tile inherent structure of the mind, or the innate laws of thought, is what Kant calls "transcendental philosophy," because it is a problem transcending sense-experience. "I call knowledge transcendental which is occupied not so much with objects, as with our a priori concepts of objects."-with our modes of correlating our experience into knowledge. There are two grades or stages in this process of working up the raw material of sensation into the finished product of thought. The first stage is the coordination of sensations by applying to them the forms of perception-space and time; the second stage is the coordination of the perceptions so developed, by applying to them the forms of conception-the "categories" of thought. Kant, using the word esthetic in its original and| etymological sense, as connoting sensation or feeling, calls the study of the first of these stages "Transcendental Esthetic"; and using the word logic as meaning the science of the forms of thought, he calls the study of the second stage "Transcendental Logic." These are terrible words, which will take meaning as the argument proceeds; once over this hill, the road to Kant will be comparatively clear.Now just what is meant by sensations and perceptions?-and how does the mind change the former into the latter? By itself a sensation is merely the awareness of a stimulus; we have a taste on the tongue, an odor in the nostrils, a sound in the ears, a temperature on the skin, a flash of light on the retina, a pressure on the fingers: it is the raw crude beginning of experience; it is what the infant has in the early days of its groping mental life; it is not yet knowledge. But let these various sensations group themselves about an object in space and time-say this apple; let the odor in the nostrils, and the taste on the tongue, the light on the retina, the shape-revealing pressure on the fingers and the hand, unite and group themselves about this "thing": and there is now an awareness not so much of a stimulus as of a specific object; there is a perception. Sensation has passed into knowledge.

But again, was this passage, this grouping, automatic? Did the sensations of themselves, spontaneously and naturally, fall into a cluster and an order, and so become perception Yes, said Locke and Hume; not at all, says Kant.

For these varied sensations come to us through varied channels of sense, through a thousand "afferent nerves" that pass from skin and eye and ear and tongue into the brain; what a medley of messengers they must be as they crowd into the chambers of the mind, calling for attention! No wonder Plato spoke of "the rabble of the senses." And left to themselves, they remain rabble, a chaotic "manifold," pitifully impotent, waiting to be ordered into meaning and purpose and power. As readily might the messages brought to a general from a thousand sectors of the battle-line weave themselves unaided into comprehension and command. No; there is a law-giver for this mob, a directing and coordinating power that does not merely receive, but takes these atoms of sensation and moulds them into sense.

Observe, first, that not all of the messages are accepted. Myriad forces play upon your body at this moment;; a storm of stimuli beats down upon the nerve-endings which, amoebalike, you put forth to experience the external world: but not all that call are chosen; only those sensations are selected that can be moulded into perceptions suited to your present purpose, or that bring those imperious messages of danger which are always relevant. The clock is ticking, and you do not hear it; but that same ticking, not louder than before, will be heard at once if your purpose wills it so. The mother asleep at her infant's cradle is deaf to the turmoil of life about her; but let the little one move, and the mother gropes her way back to waking attention like a diver rising hurriedly to the surface of the sea. Let the purpose be addition, and the stimulus "two and three" brings the response, "five"; let the purpose be multiplication, and the same stimulus, the same auditory sensations, "two and three," bring the response, "six." Association of sensations or ideas is not merely by contiguity in space or time, nor by similarity, nor by recency, frequency or intensity of experience; it is above all determined by the purpose of the mind. Sensations and thoughts are servants, they await our call, they do not come unless we need them. There is an agent of selection and direction that uses them and is their master. In addition to the sensations and the ideas there is the mind.

This agent of selection and coordination, Kant thinks, uses first of all two simple methods for the classification of the material presented to it: the sense of space, and the sense of time. As the general arranges the messages brought him according to the place for which they come, and the time at which they were written, and so finds an order and a system for them all; so the mind allocates its sensations in space and time, attributes them to this object here or that object there, to this present time or to that past. Space and time are not things perceived, but modes of perception, ways of putting sense into sensation; space and time are organs of perception.

They are a priori, because all ordered experience involves and presupposes them. Without them, sensations could never grow into perceptions. They are a priori because it is inconceivable that we should ever have any future experience that will not also involve them. And because they are a priori, their laws, which are the laws of mathematics, are a priori, absolute and necessary, world without end. It is not merely probable, it is certain that we shall never find a straight line that is not the shortest distance between two points. Mathematics, at least, is saved from the dissolvent scepticism of David Hume.

Can all the sciences be similarly saved? Yes, if their basic principle, the law of causality-that a given cause must always be followed by a given effect-can be shown, like space and time, to be so inherent in all the processes of understanding that no future experience can be conceived that would violate or escape it. Is causality, too, a priori, an indispensable prerequisite and condition of all thought?

2. - Transcendental Analytic

So we pass from the wide field of sensation and perception to the dark and narrow chamber of thought; from "transcendental esthetic" to "transcendental logic." And first to the naming and analysis of those elements in our thought which are not so much given to the mind by perception as given to perception by the mind; those levers which raise the "perceptual" knowledge of objects into the "conceptual" knowledge of relationships, sequences, and laws; those tools of the mind which refine experience into science. Just as perceptions arranged sensations around objects in space and time, so conception arranges perceptions (objects and events) about the ideas of cause, unity, reciprocal relation, necessity, contingency, etc.; these and other "categories" are the structure into which perceptions are received, and by which they are classified and moulded into the ordered concepts of thought. These are the very essence and character of the mind; mind is the coordination of experience.

And here again observe the activity of this mind that was, to Locke and Hume, mere "passive wax" under the blows of sense-experience. Consider a system of thought like Aristotle's; is it conceivable that this almost cosmic ordering of data should have come by the automatic, anarchistic spontaneity of the data themselves? See this magnificent card-catalogue in the library, intelligently ordered into sequence by human purpose. Then picture all these card-cases thrown upon the floor, all these cards scattered pell-mell into riotous disorder. Can you now conceive these scattered cards pulling themselves up, Munchausen-like, from their disarray, passing quietly into their alphabetical and topical places in their proper boxes, and each box into its fit place in the rack,-until all should be order and sense and purpose again? What a miracle-story these sceptics have given us after all!

Sensation is unorganized stimulus, perception is organized sensation, conception is organized perception, science is organized knowledge, wisdom is organized life: each is a greater degree of order, and sequence, and unity. Whence this order, this sequence, this unity? Not from the things themselves; for they are known to us only by sensations that come through a thousand channels at once in disorderly multitude; it is our purpose that put order and sequence and unity upon this importunate lawlessness; it is ourselves, our personalities, our minds, that bring light upon these seas. Locke was wrong when he said, "There is nothing in the intellect except what was first in the senses"; Leibnitz was right when he added,-"nothing, except the intellect itself." "Perceptions without conceptions," says Kant, "are blind." If perceptions wove themselves automatically into ordered thought, if mind were not an active effort hammering out order from chaos, how could the same experience leave one man mediocre, and in a more active and tireless soul be raised to the light of wisdom and the beautiful logic of truth?

The world, then, has order, not of itself, but because the thought that knows the world is itself an ordering, the first stage in that classification of experience which at last is science and philosophy. The laws of thought are also the laws of things, for things are known to us only through this thought that must obey these laws, since it and they are one; in effect, as Hegel was to say, the laws of logic and the laws of nature are one, and logic and metaphysics merge. The generalized principles of science are necessary because they are ultimately laws of thought that are involved and presupposed in every experience, past, present, and to come. Science is absolute, and truth is everlasting.

3. - Transcendental Dialectic

Nevertheless, this certainty, this absoluteness, of the highest generalizations of logic and science, is, paradoxically, limited and relative: limited strictly to the field of actual experience, and relative strictly to our human mode of experience. For if our analysis has been correct, the world as we know it is a construction, a finished product, almost-one might say-a manufactured article, to which the mind contributes as much by its moulding forms as the thing contributes by its stimuli. (So we perceive the top of the table as round, whereas our sensation is of an ellipse.) The object as it appears to us is a phenomenon, an appearance, perhaps very different from the external object before it came within the ken of our senses; what that original object was we can never know; the "thing-in-itself" may be an object of thought or inference (a "noumenon"), but it cannot be experienced,-for in being experienced it would be changed by its passage through sense and thought. "It remains completely unknown to us what objects may be by themselves and apart from the re-ceptivity of our senses. We know nothing but our manner of perceiving them; that manner being peculiar to us, and not necessarily shared by every being, though, no doubt, by every human being." [If Kant had not added the last clause, his argument for the necessity of knowledge would have fallen.] The moon as known to us is merely a bundle of sensations (as Hume saw), unified (as Hume did not see) by our native mental structure through the elaboration of sensations into perceptions, and of these into conceptions or ideas; in result, the moon is for us merely our ideas. [So John Stuart Mill, with all his English tendency to realism, was driven at last to define matter as merely "a permanent possibility of sensations."]

Not that Kant ever doubts the existence of "matter" and the external world; but he adds that we know nothing certain about them except that they exist. Our detailed knowledge is about their appearance, their phenomena, about the sensations which we have of them. Idealism does not mean, as the man in the street thinks, that nothing exists outside the perceiving subject; but that a goodly part of every object is created by the forms of perception and understanding: we know the object as transformed into idea; what it is before being so transformed we cannot know. Science, after all, is naive; it supposes that it is dealing with things in themselves, in their full-blooded external and uncorrupted reality; philosophy is a little more sophisticated, and realizes that the whole material of science consists of sensations, perceptions and conceptions, rather than of things. "Kant's greatest merit," says Schopenhauer, "is the distinction of the phenomenon from the thing-in-itself."

It follows that any attempt, by either science or religion, to say just what the ultimate reality is, must fall back into mere hypothesis; "the understanding can never go beyond the limits of sensibility." Such transcendental science loses itself in "antinomies," and such transcendental theology loses itself in "paralogisms." It is the cruel function of "transcendental dialectic" to examine the validity of these attempts of reason to escape from the enclosing circle of sensation and appearance into the unknowable world of things "in themselves."

Antinomies are the insoluble dilemmas born of a science that tries to overleap experience. So, for example, when knowledge attempts to decide whether the world is finite or infinite in space, thought rebels against either supposition: beyond any limit, we are driven to conceive something further, endlessly; and yet infinity is itself inconceivable. Again: did the world have a beginning in time? We cannot conceive eternity; but then, too, we cannot conceive any point in the past without feeling at once that before that, something was. Or has that chain of causes which science studies, a beginning, a First Cause? Yes, for an endless chain is inconceivable; no, for a first cause uncaused is inconceivable as well. Is there any exit from these blind alleys of thought? There is, says Kant, if we remember that space, time and cause are modes of perception and Conception, which must enter into all our experience, since they are the web and structure of experience; these dilemmas arise from supposing that space, time and cause are external things independent of perception. We shall never have any experience which we shall not interpret in terms of space and time and cause; but we shall never have any philosophy if we forget that these are not things, but modes of interpretation and understanding.

So with the paralogisms of "rational" theology-which attempts to prove by theoretical reason that the soul is an incorruptible substance, that the will is free and above the law of cause and effect, and that there exists a "necessary being," God, as the presupposition of all reality. Transcendental dialectic must remind theology that substance and cause and necessity are finite categories, modes of arrangement and classification which the mind applies to sense-experience, and reliably valid only for the phenomena that appear to such experience; we cannot apply these conceptions to the noumenal (or merely inferred and conjectural) world. Religion cannot be proved by theoretical reason.

————————

So the first Critique ends. One could well imagine David Hume, uncannier Scot than Kant himself, viewing the results with a sardonic smile. Here was a tremendous book, eight hundred pages long; weighted beyond bearing, almost, with ponderous terminology; proposing to solve all the problems of metaphysics, and incidentally to save the absoluteness of science and the essential truth of religion. What had the book really done? It had destroyed the naive world of science, and limited it, if not in degree, certainly in scope,-and to a world confessedly of mere surface and appearance, beyond which it could issue only in farcical "antinomies"; so science was "saved"! The most eloquent and incisive portions of the book had argued that the objects of faith-a free and immortal soul, a benevolent creator-could never be proved by reason; so religion was "saved"! No wonder the priests of Germany protested madly against this salvation, and revenged themselves by calling their dogs Immanuel Kant.

And no wonder that Heine compared the little professor of Konigsberg with the terrible Robespierre; the latter had merely killed a king, and a few thousand Frenchmen-which a German might forgive; but Kant, said Heine, had killed God, had undermined the most precious arguments of theology. "What a sharp contrast between the outer life of this man, and his destructive, world-convulsing thoughts! Had the citizens of Konigsberg surmised the whole significance of those thoughts, they would have felt a more profound awe in the presence of this man than in that of an executioner, who merely slays human beings. But the good people saw in him nothing but a professor of philosophy; and when at the fixed hour he sauntered by, they nodded a friendly greeting, and set their watches."

Was this caricature, or revelation?

The Story of Philosophy

The Lives and Opinions of the Great

Philosophers of the Western World

by WILL DURANT

http://www.amazon.com/exec/obidos/tg/detail/-/0671739166/

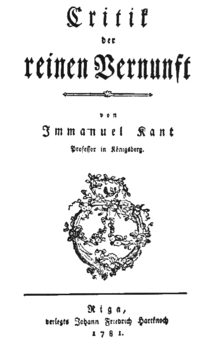

Critique of Pure Reason

Title page of the 1781 edition

|

|

| Author | Immanuel Kant |

|---|---|

| Original title | Critik a der reinen Vernunft |

| Translator | see below |

| Country | Germany |

| Language | German |

| Subject | Metaphysics |

| Published | 1781 |

| Pages | 856 (first German edition)[1] |

| a Kritik in modern German. | |

| Part of a series on |

| Immanuel Kant |

|---|

|

|

Category • |

Critique of Pure Reason (German: Kritik der reinen Vernunft; 1781; second edition 1787) is a book by the German philosopher Immanuel Kant, in which the author seeks to determine the limits and scope of metaphysics. Also referred to as Kant's "First Critique", it was followed by his Critique of Practical Reason (1788) and Critique of Judgment (1790). In the preface to the first edition, Kant explains that by a "critique of pure reason" he means a critique "of the faculty of reason in general, in respect of all knowledge after which it may strive independently of all experience" and that he aims to reach a decision about "the possibility or impossibility of metaphysics."

Kant builds on the work of empiricistphilosophers such as John Locke and David Hume, as well as rationalist philosophers such as Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz and Christian Wolff. He expounds new ideas on the nature of space and time, and tries to provide solutions to the skepticism of Hume regarding knowledge of the relation of cause and effect and that of René Descartes regarding knowledge of the external world. This is argued through the transcendental idealism of objects (as appearance) and their form of appearance. Kant regards the former "as mere representations and not as things in themselves", and the latter as "only sensible forms of our intuition, but not determinations given for themselves or conditions of objects as things in themselves". This grants the possibility of a priori knowledge, since objects as appearance "must conform to our cognition...which is to establish something about objects before they are given to us." Knowledge independent of experience Kant calls "a priori" knowledge, while knowledge obtained through experience is termed "a posteriori."[2] According to Kant, a proposition is a priori if it is necessary and universal. A proposition is necessary if it could not possibly be false, and so cannot be denied without contradiction. A proposition is universal if it is true in all cases, and so does not admit of any exceptions. Knowledge gained a posteriori through the senses, Kant argues, never imparts absolute necessity and universality, because it is always possible that we might encounter an exception.[3]

Kant further elaborates on the distinction between "analytic" and "synthetic" judgments.[4] A proposition is analytic if the content of the predicate-concept of the proposition is already contained within the subject-concept of that proposition.[5] For example, Kant considers the proposition "All bodies are extended" analytic, since the predicate-concept ('extended') is already contained within—or "thought in"—the subject-concept of the sentence ('body'). The distinctive character of analytic judgements was therefore that they can be known to be true simply by an analysis of the concepts contained in them; they are true by definition. In synthetic propositions, on the other hand, the predicate-concept is not already contained within the subject-concept. For example, Kant considers the proposition "All bodies are heavy" synthetic, since the concept 'body' does not already contain within it the concept 'weight'.[6]Synthetic judgments therefore add something to a concept, whereas analytic judgments only explain what is already contained in the concept.

Prior to Kant, it was thought that all a priori knowledge must be analytic. Kant, however, argues that our knowledge of mathematics, of the first principles of natural science, and of metaphysics, is both a priori and synthetic. The peculiar nature of this knowledge cries out for explanation. The central problem of the Critique is therefore to answer the question: "How are synthetic a priori judgements possible?"[7] It is a "matter of life and death" to metaphysics and to human reason, Kant argues, that the grounds of this kind of knowledge be explained.[7]

Though it received little attention when it was first published, the Critique later attracted attacks from both empiricist and rationalist critics, and became a source of controversy. It has exerted an enduring influence on Western philosophy, and helped bring about the development of German idealism. The book is considered a culmination of several centuries of early modern philosophy and an inauguration of modern philosophy.

No comments:

Post a Comment