Pre-Socratic Philosophers

Thales of Miletus initiated the intellectual movement that produced the works now known as ancient Greek philosophy by inquiring into the First Cause of existence, the matter from which all else came, which was also the causative factor in its becoming. He concluded that water was the First Cause because it could assume different forms (steam when heated, ice when frozen) and seemed to inform all living things.

This conclusion was rejected by later philosophers beginning with Anaximander (l. c. 610 - c. 546 BCE) who argued that the First Cause was beyond matter and was, in fact, a cosmic force of creative energy constantly making, destroying, and remaking the observable world. The philosophers who followed these two all established their own schools of thought with their own concepts of a First Cause, steadily building on the accomplishments of predecessors until philosophy found full expression and depth in the works of Plato (l. 428/427-348/347 BCE), who attributed his own ideas to the figure of Socrates.

The philosophy of the Pre-Socratic philosophers is by no means uniform. No two of the men supported exactly the same ideas (except for Parmenidesand Zeno of Elea), and most criticized the earlier works of others even as they used them to develop their own concepts. Plato, finally, is critical of almost all of them, but it is apparent from his work that their schools of thought informed and influenced his own, notably the philosophic-religious vision of Pythagoras.

The works of Plato and his student Aristotle (l. 384-322 BCE) would go on to inform the three great monotheistic religions of the present day – Judaism, Christianity, and Islam – as well as Western civilization overall, and these would not have been possible if not for the Pre-Socratic philosophers.

Pre-Socratics & Their Contributions

There are over 90 Pre-Socratic philosophers, all of whom contributed something to world knowledge, but scholar Forrest E. Baird has pared that number down to a more manageable 15 major thinkers whose contributions directly or indirectly influenced Greek culture and the later works of Plato and Aristotle:

- Thales of Miletus – l. c. 585 BCE

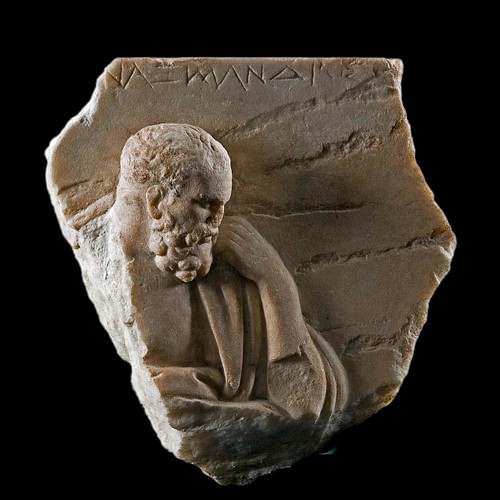

- Anaximander – l. c. 610 - c. 546 BCE

- Anaximenes – l. c. 546 BCE

- Pythagoras – l. c. 571 - c. 497 BCE

- Xenophanes of Colophon – l. c. 570 - c. 478 BCE

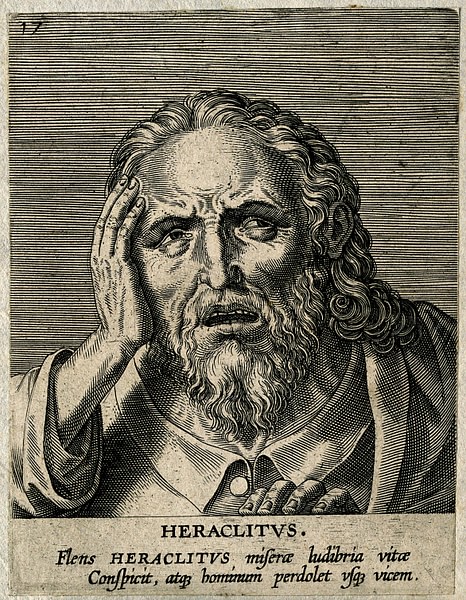

- Heraclitus of Ephesus – l. c. 500 BCE

- Parmenides – l. c. 485 BCE

- Zeno of Elea – l. c. 465 BCE

- Empedocles – l. c. 484-424 BCE

- Anaxagoras – l. c. 500 - c. 428 BCE

- Democritus – l. c. 460 - c. 370 BCE

- Leucippus – l. c. 5th century BCE

- Protagoras – l. c. 485-415 BCE

- Gorgias – l. c. 427 BCE

- Critias - c. 460-403 BCE

Thales: According to Aristotle, Thales was the first to ask, "What is the basic 'stuff' of the universe?" (Baird, 8) as in, what was the First Cause of existence, from what element or force did everything else proceed? Thales claimed it was water because whatever the First Cause was had to be a part of everything that followed. When water was heated it became air (vapor), when it was cooled it became a solid (ice), added to earth, it became mud and, once dried, it became solid again, under pressure, it could move rocks, while at rest, it provided a habitat for other living things and was essential to human life. It seemed clear to Thales, then, that the underlying element of creation had to be water.

Anaximander: It was not clear to Anaximander, however, who expanded the definition of the First Cause with his higher concept of the apeiron – “the unlimited, boundless, infinite, or indefinite” (Baird, 10) – which was an eternal creative force bringing things into existence according to a natural, set pattern, destroying them and recreating them in new forms. No natural element could be the First Cause, he claimed, because all natural elements must have originated from an earlier source. Once created, he claimed, creatures then evolved to adapt to their environment and so he first suggested the Theory of Evolution over 2,000 years before Darwin.

Anaximenes: Anaximenes, thought to be Anaximander's student, claimed air as the First Cause. Baird comments:

Anaximenes proposed air as the basic world principle. While at first his thesis may seem a step backwards from the more comprehensive (like Anaximander's unlimited) to the less comprehensive particular (like Thales' water), Anaximenes added an important point. He explained a process by which the underlying one (air) becomes the observable many: By rarefaction, air becomes fire, and, by condensation, air becomes, successively, wind, water, and earth. Observable qualitative differences (fire, wind, water, earth) are the result of quantitative changes, that is, of how densely packed is the basic principle. This view is still held by scientists. (12)

Anaximenes' definition of “air” and its mutations suggested a First Cause which defined life as a constant state of flux, of change. As air became rarefied or condensed or so on, it changed in form; therefore, change was an important element of the First Cause.

Pythagoras: This concept was developed further by Pythagoras who claimed number – mathematics - as the underlying principle of Truth. In the same way that number has no beginning or ending, neither does creation. The concept of transformation is central to the Pythagorean vision; the human soul, Pythagoras claimed, is immortal, passing through many different incarnations, life after life, as it acquires new knowledge of the world as experienced in different forms. Pythagoras' concepts – including his famous Pythagorean Theorem – were definitely developed from Egyptian ideas, but he reworked these to make them distinctly his own. He wrote nothing down and so much of his thought has been lost, but from what is known, it is clear his concept of the Transmigration of Souls (reincarnation) greatly influenced Plato's belief regarding immortality.

Xenophanes: The concept of an eternal soul suggested some governing force which created it and to which that soul would one day return after death. Pythagoras included this concept in his teachings which focused on personal salvation through spiritual discipline but does not define what that force is. Xenophanes would later fill in this blank with his concept of a single God. He writes:

There is one god, among gods and men the greatest, not at all like mortals in body or in mind. He sees as a whole, thinks as a whole, and hears as a whole. But without toil, he sets everything in motion by the thought of his mind. (DK 23-25, Freeman, 23)

Xenophanes denied the validity of the anthropomorphic gods of Greece in arguing for a single spiritual entity which had created all things and set them in motion. Once in motion, human beings continued on a course until death at which time, he seems to suggest, their souls reunite with the creative force. Xenophanes' monotheism was not met with any antagonism from the religious authorities of his time because he couched his claims in poetry and alluded to a single god among others, who could have been interpreted as Zeus.

Heraclitus: His younger contemporary, Heraclitus, rejected this view and replaced “God” with “Change”. He is best known for the phrase Panta Rhei (“everything changes” or “life is flux”) and the adage that “one can never step into the same river twice” alluding to the fact that everything, always, is in motion and the water of the river changes moment to moment, as does life. To Heraclitus, existence was brought into being and sustained through a clash of opposites which continually encouraged transformation – day and night, the seasons, etc. – so that everything was always in continual motion and a state of perpetual change. Strife and war, to Heraclitus, were necessary aspects of life in that they embodied the concept of transformative change. To resist this change meant resisting life; accepting change encouraged a peaceful and untroubled life.

Parmenides: Parmenides rejected this view of life as change in his Eleatic School of thought which taught Monism, the belief that all of observable reality is of one single substance, uncreated, and indestructible. Change is an illusion; appearances change, but not the essence of reality which is shared by every human being. That which one experiences and fears as “change” is illusory because all living things share in the same essential essence. One cannot trust the senses to interpret a reality which suggests change, he said, because the senses are unreliable. One must, instead, recognize that “there is a way which is and a way which is not” (a way of fact and a way of opinion) and recognize the essential Oneness of material existence which does not differentiate: humans grow and develop and die just as animals and plants do. What people see as “differences” between themselves and others are only minor details.

Zeno of Elea: Parmenides' thought was defended and defined by his pupil Zeno of Elea who created a series of logical paradoxes proving that plurality was an illusion of the senses and reality was uniform. There was actually no such thing as change, Zeno showed, only the illusion of change. He proved this through 40 paradoxes of which only a handful have survived. The most famous of these is known as the Race Course, which stipulates that between Point A and Point Z on a course, one must first run halfway. Between Point A and that halfway mark is another halfway mark and between Point A and that other halfway mark is still another and then another. One can never reach Point Z because one cannot, logically, reach that point without first reaching the halfway mark which one cannot reach because of the many “halfway marks” which precede it. Movement, then, is an illusion and so, therefore, is change because, in order for anything to change, it would have to alter the nature of reality – it would have to remove all “halfway marks” – and this is a logical absurdity. Through this paradox, and his many others, Zeno proved, mathematically, that Parmenides' claims were true.

Empedocles: Empedocles completely rejected the claim that change was an illusion and believed that plurality was the essential nature of existence. All things were differentiated in their own unique way, and by the meeting of opposites, creative energies were released, which led to transformation. Baird writes:

Empedocles sought to reconcile Heraclitus' insistence on the reality of change with the Eleatic claim that generation and destruction are unthinkable. Going back to the Greeks' traditional belief in the four elements, he found a place for Thales' water, Anaximenes' air, and Heraclitus' fire, and he added earth as the fourth. In addition to these four elements, which Aristotle would later call “material causes”, Empedocles postulated two “efficient causes”: strife and love. (31-32)

Strife, to Empedocles, differentiated the things of the world and defined them; love brought them together and joined them. The opposing forces of strife and love, then, worked together toward a unity of design and wholeness, which, Empedocles believed, was what the Eleatic school of Parmenides was trying, but failed, to say.

Anaxagoras: Anaxagoras took this idea of opposites and definition and developed his concept of like-and-not-like and “seeds”. Nothing can come from what it is not like and everything must come from something; this “something” is particles (“seeds”) which constitute the nature of that particular thing. Hair, for example, cannot grow from stone but only from the particles conducive to hair growth. All things proceeded from natural causes, he said, even if those causes are not clear to people. He publicly refuted the concept of the Greek gods and rejected religious explanations, ascribing phenomena to natural causes, and he is the first philosopher to be condemned by a legal body (the court of Athens) for his beliefs. He was saved from execution by the statesman Pericles (l. 495-429 BCE) and lived the rest of his life in exile at Lampsacus.

Leucippus and Democritus: His ”seed” theory would influence the development of the concept of the atom by Leucippus and his student Democritus who claimed that the entire universe is made up of “un-cutables” known as atamos. Atoms come together to form the observable world, taking now the form of a chair, now of a tree, now of a human being, but the atoms themselves are of one substance, unchanging, and indestructible; when one form they take is destroyed, they simply assume another. The theory of the atomic universe encouraged Leucippus' philosophy on the supremacy of fate over free will.

Leucippus is best known for the one line which can be authoritatively attributed to him: “Nothing happens at random; everything happens out of reason and by necessity” (Baird, 39). Since the universe is composed of atoms, and atoms are indestructible and continually change form, and human beings are part of this process, the life of an individual is driven by forces outside of one's control – one cannot stop the process of atoms changing form – and so one's fate was preordained and free will was illusory. What one could change through one's will could in no way prevent one's inevitable dissolution.

The Sophists, Socrates, & Plato

As Greek intellectual thought developed, it gave rise to the profession of the Sophist, teachers of rhetoric who taught the sons of the upper class the philosophies of the Pre-Socratics and, through their concepts, the art of persuasion and how to win any argument. Ancient Greece, especially Athens, was highly litigious, and lawsuits were a daily occurrence; knowing how to sway a jury to one's side was considered as valuable a skill at that time as it is today, and Sophists were highly paid.

There were many famous Sophists, such as Thrasymachus (l. c. 459 - c. 400 BCE), best known as Socrates' antagonist in Book I of Plato's Republic and Hippias of Elis (l. 5th century BCE), another contemporary of Socrates and one of the highest-paid Sophists of the time. The three most famous, however, are Protagoras, Gorgias, and Critias whose central arguments would later be developed by other Western philosophers to support the claims of relativism, skepticism, and atheism.

Protagoras: Protagoras of Abdera is best known for the claim which is most commonly given as “man is the measure of all things” meaning that everything is relative to individual interpretation. To one person, who is used to warm climates, a room will feel cold while to another, used to cold climates, it will be warm; neither, according to Protagoras is objectively “right” or objectively “wrong” but are both right according to their experiences and interpretation. Protagoras never denied the existence of the gods but claimed no human being could say anything about them definitively because there was simply no way one could have such knowledge. The existence of the gods and whatever their will might be, like everything else in life, was up to each individual to decide and, whatever they decided, that was the truth for them.

Gorgias: Gorgias claimed that there is no such thing as “knowledge” and that what passed for “knowledge” was only opinion. Actual knowledge was incomprehensible and incommunicable. Gorgias laid out his claim in detail to show that what people called Being could not really exist because anything that “is” must have a beginning and what people called Being had no known First Cause – only people's opinions on what might be a First Cause – and therefore Being could not logically exist. What people perceived as “reality” was neither Being nor Not-Being but simply What-is, but what exactly What-is constituted was unknowable and, if one should know it, could not be communicated to others because they would not be able to understand.

Critias: Critias was related to Plato (his mother's cousin) and an early follower of Socrates. He was one of the Thirty Tyrants who overthrew the Athenian democracy, and the fact he had been Socrates' student is thought to have gone against the latter at his trial for impiety in 399 BCE. Critias is best known for his argument that religion was created by strong and clever men to control others. In a long poem, he describes a time of lawlessness when reasonable men tried to impose order but could not. They decided to create a fiction in which supernatural entities existed who could see into the hearts of men and judge them, sending untold punishments upon those who defied order. In time, this fiction became ritualized as religion but, in reality, there were no such things as gods, no afterlife, and no meaning to religious ritual.

Plato would address the claims of most of the Pre-Socratics, in whole or in part, throughout his works. Pythagoras' thought, especially, had a significant impact on the development of Plato's theory of the immortality of the soul, the afterlife, and memory as recollection from a past life. Protagoras' relativism, the antithesis of Plato's idealism, inspired and encouraged many of his dialogues. It could be argued, in fact, that all of Plato's work is a direct refutation of Protagoras but the concepts of all of the Pre-Socratics inform Plato's work to varying degrees and, in so doing, contributed the underlying foundation for the development of Western philosophy.

Phases of Presocratic Philosophy

According to Philip Wheelwright histories of ancient philosophy conceive the course of early Greek metaphysics as falling into four main stages. The main direction of Presocratic thought may be said to fall into the following fourfold schema.

The First Stage

Represented by the Milesians

The three philosophers of Miletus (Thales, Anaximander, Anaximenes) sought a principle by which the nature of the world could be explained, and gradually they became more and more conscious of the question of becoming—of how the initial substance, whether water or air or an unlimited reservoir of potential qualities, could transform itself into existing things and qualities so numerous and various.

The Second Stage

Heraclitus carried the idea of becoming to the ultimate extreme, denying the existence of any unchanging substance, and declaring that everything without exception is subject to change—faster or slower, but in any case unremitting and inevitable.

The Third Stage

Represented by the Eleatic school.

Parmenides (followed by Zeno and Melissus, the other principle members of the Eleatic school) opposed the doctrine of universal flux by going to the opposite extreme and dismissing all change as necessarily unreal and illusory, holding it to be rationally inconceivable that what was not should begin to be or that what was should cease to be. What truly is, he argued, must be what it is independently of time; hence only Being can exist and all becoming is illusory. The other two Eleatics differ from Parmenides only in approach and details.

The Fourth Stage

The metaphysical reconstructionists who followed Parmenides are Empedocles, Anaxagoras, and the atomist Leucippus and Democritus. Despite the large differences among them they share the same general attempt to reconcile Parmenides’ principle, that reality must be one and changeless, with the obvious fact of plurality and ongoing change. This they do by postulating a plurality of unchanging basic entities, and hence explaining the changes that we see going on around us as change relations among those primal entities.

The Presocratics | Mt. San Antonio College

https://faculty.mtsac.edu/cmcgruder/presocratics.html

What is “Mythos” and “Logos”?

by m.servetus

The terms “mythos” and “logos” are used to describe the transition in ancient Greek thought from the stories of gods, goddesses, and heroes (mythos) to the gradual development of rational philosophy and logic (logos). The former is represented by the earliest Greek thinkers, such as Hesiod and Homer; the latter is represented by later thinkers called the “pre-Socratic philosophers” and then Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle. (See the book: From Myth to Reason? Studies in the Development of Greek Thought).

In the earliest, “mythos” stage of development, the Greeks saw events of the world as being caused by a multitude of clashing personalities — the “gods.” There were gods for natural phenomena such as the sun, the sea, thunder and lightening, and gods for human activities such as winemaking, war, and love. The primary mode of explanation of reality consisted of highly imaginative stories about these personalities. However, as time went on, Greek thinkers became critical of the old myths and proposed alternative explanations of natural phenomena based on observation and logical deduction. Under “logos,” the highly personalized worldview of the Greeks became transformed into one in which natural phenomena were explained not by invisible superhuman persons, but by impersonal natural causes.

However, many scholars argue that there was not such a sharp distinction between mythos and logos historically, that logos grew out of mythos, and elements of mythos remain with us today.

For example, ancient myths provided the first basic concepts used subsequently to develop theories of the origins of the universe. We take for granted the words that we use every day, but the vast majority of human beings never invent a single word or original concept in their lives — they learn these things from their culture, which is the end-product of thousands of years of speaking and writing by millions of people long-dead. The very first concepts of “cosmos,” “beginning,” nothingness,” and differentiation from a single substance — these were not present in human culture for all time, but originated in ancient myths. Subsequent philosophers borrowed these concepts from the myths, while discarding the overly-personalistic interpretations of the origins of the universe. In that sense, mythos provided the scaffolding for the growth of philosophy and modern science. (See Walter Burkert, “The Logic of Cosmogony” in From Myth to Reason: Studies in the Development of Greek Thought.)

An additional issue is the fact that not all myths are wholly false. Many myths are stories that communicate truths even if the characters and events in the story are fictional. Socrates and Plato denounced many of the early myths of the Greeks, but they also illustrated philosophical points with stories that were meant to serve as analogies or metaphors. Plato’s allegory of the cave, for example, is meant to illustrate the ability of the educated human to perceive the true reality behind surface impressions. Could Plato have made the same philosophical point in a literal language, without using any stories or analogies? Possibly, but the impact would be less, and it is possible that the point would not be effectively communicated at all.

Some of the truths that myths communicate are about human values, and these values can be true even if the stories in which the values are embedded are false. Ancient Greek religion contained many preposterous stories, and the notion of personal divine beings directing natural phenomena and intervening in human affairs was false. But when the Greeks built temples and offered sacrifices, they were not just worshiping personalities — they were worshiping the values that the gods represented. Apollo was the god of light, knowledge, and healing; Hera was the goddess of marriage and family; Aphrodite was the goddess of love; Athena was the goddess of wisdom; and Zeus, the king of the gods, upheld order and justice. There’s no evidence at all that these personalities existed or that sacrifices to these personalities would advance the values they represented. But a basic respect for and worshipful disposition toward the values the gods represented was part of the foundation of ancient Greek civilization. I don’t think it was a coincidence that the city of Athens, whose patron goddess was Athena, went on to produce some of the greatest philosophers the world has seen — love of wisdom is the prerequisite for knowledge, and that love of wisdom grew out of the culture of Athens. (The ancient Greek word philosophia literally means “love of wisdom.”)

It is also worth pointing out that worship of the gods, for all of its superstitious aspects, was not incompatible with even the growth of scientific knowledge. Modern western medicine originated in the healing temples devoted to the god Asclepius, the son of Apollo, and the god of medicine. Both of the great ancient physicians Hippocrates and Galen are reported to have begun their careers as physicians in the temples of Asclepius, the first hospitals. Hippocrates is widely regarded as the father of western medicine and Galen is considered the most accomplished medical researcher of the ancient world. As love of wisdom was the prerequisite for philosophy, reverence for healing was the prerequisite for the development of medicine.

Karen Armstrong has written that ancient myths were never meant to be taken literally, but were “metaphorical attempts to describe a reality that was too complex and elusive to express in any other way.” (A History of God) I am not sure that’s completely accurate. I think it most likely that the mass of humanity believed in the literal truth of the myths, while educated human beings understood the gods to be metaphorical representations of the good that existed in nature and humanity. Some would argue that this use of metaphors to describe reality is deceptive and unnecessary. But a literal understanding of reality is not always possible, and metaphors are widely used even by scientists.

Theodore L. Brown, a professor emeritus of chemistry at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, has provided numerous examples of scientific metaphors in his book, Making Truth: Metaphor in Science. According to Brown, the history of the human understanding of the atom, which cannot be directly seen, began with a simple metaphor of atoms as billiard balls; later, scientists compared atoms to plum pudding; then they compared the atom to our solar system, with electrons “orbiting” around a nucleus. There has been a gradual improvement in our models of the atom over time, but ultimately, there is no single, correct literal representation of the atom. Each model illustrates an aspect or aspects of atomic behavior — no one model can capture all aspects accurately. Even the notion of atoms as particles is not fully accurate, because atoms can behave like waves, without a precise position in space as we normally think of particles as having. The same principle applies to models of the molecule as well. (Brown, chapters, 4-6) A number of scientists have compared the imaginative construction of scientific models to map-making — there is no single, fully accurate way to map the earth (using a flat surface to depict a sphere), so we are forced to use a variety of maps at different scales and projections, depending on our needs.

Sometimes the visual models that scientists create are quite unrealistic. The model of the “energy landscape” was created by biologists in order to understand the process of protein folding — the basic idea was to imagine a ball rolling on a surface pitted with holes and valleys of varying depth. As the ball would tend to seek out the low points on the landscape (due to gravity), proteins would tend to seek the lowest possible free energy state. All biologists know the energy landscape model is a metaphor — in reality, proteins don’t actually go rolling down hills! But the model is useful for understanding a process that is highly complex and cannot be directly seen.

What is particularly interesting is that some of the metaphorical models of science are frankly anthropomorphic — they are based on qualities or phenomena found in persons or personal institutions. Scientists envision cells as “factories” that accept inputs and produce goods. The genetic structure of DNA is described as having a “code” or “language.” The term “chaperone proteins” was invented to describe proteins that have the job of assisting other proteins to fold correctly; proteins that don’t fold correctly are either treated or dismantled so that they do not cause damage to the larger organism — a process that has been given a medical metaphor: “protein triage.” (Brown, chapters 7-8) Even referring to the “laws of physics” is to use a metaphorical comparison to human law. So even as logos has triumphed over the mythos conception that divine personalities rule natural phenomena, qualities associated with personal beings have continued to sneak into modern scientific models.

The transition of a mythos-dominated worldview to a logos-dominated worldview was a stupendous achievement of the ancient Greeks, and modern philosophy, science, and civilization would not be possible without it. But the transition did not involve a complete replacement of one worldview with another, but rather the building of additional useful structures on top of a simple foundation. Logos grew out of its origins in mythos, and retains elements of mythos to this day. The compatibilities and conflicts between these two modes of thought are the thematic basis of this website.

Related: A Defense of the Ancient Greek Pagan Religion

What is “Mythos” and “Logos”? | Mythos/Logos

https://mythoslogos.org/2014/12/21/what-is-mythos-and-logos/

Mythos & Logos: Two Ways of Explaining the World

…I find it useful when discussing this distinction to consider the Greek words from which our English words “logical” and “mythical” have been derived, logos and mythos.Both Greek words can be translated as something like “story” or “account”; mythical thinking and logical thinking both provide an account of the world, but they do so in very different ways. Those using logical thinking approach the world scientifically and empirically. They look for explanations using observable facts, controlled experiments, and deductive proofs. Truth discovered through logos seeks to be objective and universal. Those using mythical thinking, on the other hand, approach the world through less direct, more intuitive means. A person might gain poetic insights into the nature of the world by seeing a caterpillar emerge from a cocoon or watching a full moon rise as the sun sets. Truth discovered through mythos is more subjective, based on individual feelings and experiences.

To illustrate the difference between these two approaches, let me consider one of nature’s most perplexing conundrums: why the turtle has a shell. A recent article in New Scientist magazine demonstrates how the techniques of logical thinking have been applied to this question. Modern turtle shells are deeply infused with the turtles’ skeletons; observations made on turtle embryos suggested that the shell might have been an outgrowth from the dorsal ribs and the vertebrae. Bone fragments recently discovered in New Mexico, however, show that this hypothesis was incorrect. The fragments came from an ancestor of the turtle with something like the armor of an armadillo; since the rows of armored plates were not connected to the skeleton, the shells of later turtles could not have been an outgrowth of it. More experiments will be performed and more observations will be made to explain the turtle’s shell in terms of physical causes and effects.

An Aesopic fable demonstrates how the techniques of mythical thinking have been applied to this same question. In a previous article, I discussed this fable of Zeus and the Turtle in great detail: Zeus invites all the animals to his wedding, but the turtle skips the wedding because she prefers being in her own home than being anywhere else; as punishment, Zeus makes her carry her house with her everywhere she goes. We do not possess any description of the thought-process involved in the creation of this fable. We could guess that some ancient person might have observed the turtle’s slow pace and understood the turtle as downcast and humiliated, struggling under its great burden — or perhaps an observer saw in the turtle great determination in the face of life’s adversities. If a story already existed of a divinity punishing a disobedient creature, the observer may have retold the story with a turtle as the disobedient character to express the insights from this observation; perhaps the events of the narrative and the explanation occurred to the observer simultaneously. We cannot know for sure the origin of this story, but something like this strikes me as a possible development.

The academic discipline of mythology is perhaps best understood as the application of the techniques of logical thinking to the products of mythical thinking; this is nicely illustrated by the fact that the English word mythology is derived from both Greek words mythos and logos. My own discussion of the Aesopic fable fits nicely within this discipline because it is an attempt to explain the fable in a objective, historical fashion. But the reverse also occurs: the techniques of mythical thinking can be applied to the products of logical thinking. Fantasy authors often incorporate scientific discoveries and theories into their stories: Philip Pullman connects dark matter with Milton in the His Dark Materials trilogy, and Madeleine L’Engle examines the space/time continuum and the theory of relativity in her Time quintet. Many science-fiction authors have scientific backgrounds and use narratives to work out for themselves and to convey to others the mythical significance of findings in their various fields.

Many of the great advances in civilization have been the product of these two ways of thinking working together. Artists, poets, musicians, and other mythical thinkers rely on the tools and techniques of logos for their own works of mythos: in a previous article, I discussed the effects of iron tools on the art of totem-pole carving. The pursuits of logos are in turn influenced by mythos: logical thinkers have figured out, for example, how to cure illnesses and prolong the average human lifespan, but they have learned through mythical thinking to value human life enough to bother. Products of logos enable us to communicate with the people who matter most to us (even when they are thousands of miles away), but mythos provides the context for us to know which people matter and what we should say to them when we do communicate. These exchanges, interactions, and dependencies demonstrate to me that mythos and logos are best seen as complementary to each other.

Though we have inherited great traditions in both mythical thinking and logical thinking, logical thinking has risen to such prominence that many no longer realize any another approach exists. The decline of mythical thinking throughout much of the industrialized world has resulted in the unfortunate loss of a sense of transcendence and of the value of human life. Some people argue that this has been responsible for much of the devastation in the last one hundred years. (I explore this connection in an article discussing Shikasta, a science-fiction novel by Doris Lessing.) I would not argue that mythical thinking can cure all of humanity’s problems — I imagine that an equal amount of damage has been done on account of both mythos and logos — but I would argue that it is now our burden and privilege to re-discover mythical thinking and to wrestle with the proper way to re-integrate these two ways of thinking into our lives.

http://journeytothesea.com/mythos-logos/

In Rereading the Sophists: Classical Rhetoric Refigured, Susan Jarratt argues that the ancient Greek sophists existed at a time when human society was shifting from mythos, an uncritical acceptance of tradition as represented in myths and stories, to logos, a system of logical analysis allowing access to certain truth, as represented in Plato and Aristotle. Jarratt introduces nomos, or “custom-law,” as a third term. She sees the sophists as using logos (words and logic) to challenge_traditional mythos in order to renegotiate nomos (cultural values and beliefs). Her model for this process is found in Gorgias’s “Encomium of Helen,” in which he argues that Helen of Troy is blameless because she acted as she did for one of four reasons: she was fated by the gods, abducted by force, persuaded by speeches, or conquered by love. Gorgias invokes the myth of Helen and uses words and arguments to challenge her bad reputation among the Greeks, influencing social attitudes toward women in general at the same time.

This sophistic triad of terms–mythos, logos, nomos–can be a productive alternative to the better known Aristotelian appeals of ethos, logos, and pathos.The advantage of the sophistic perspective created by these terms is that it directly addresses social values (nomoi), a factor that the Aristotelian terms tend to obscure...

Sophistic Appeals: Mythos, Logos, Nomos – Teaching Text Rhetorically

https://textrhet.com/2020/01/09/sophistic-appeals-mythos-logos-nomos/

Mythos and Logos - A Genealogical Approach

by Chiara Bottici

Abstract: The paper aims to put forward a critique of the common view of the birth of philosophy as the exit from myth. To this end, it proposes a genealogy of myth which starts from the observation that the two terms were originally used as synonymous. By analyzing the ways in which the two terms relate to each other in the thinking of Presocratics, Plato and Aristotle, the paper argues that up to the fourth century BC no opposition between mythos and logos was stated and that not even in Aristotle is there an identification of myth with false discourse. This, in the end, is the result of the fact that their views of truth and reality enabled a plurality of programmes of truth to coexist next to one another.

https://www.academia.edu/12897207/Mythos_and_Logos_A_Genealogical_Approach

Hesiod and Anaximander In Comparison

Ancient Greek philosophy begins in Miletus, an illustrious Greek colony along the eastern shore of the Aegean Sea. Before the Milesian philosophers, however, there were the mythic poets. The history of ancient Greek philosophy is, in some sense, a history of breaking with the strategy these poets use to explain why things are they way they are...

…We are prone nowadays to treat scientific inquiry as radically different from mythology. Comparing Hesiod and Anaximander reveals intimations of these differences. Hesiod grounds his inquiries upon private inspiration, and his explanations appeal to divine action. Anaximander, by contrast, grounds his inquiries upon public reason, and his explanations appeal to impersonal forces. Yet comparing Hesiod and Anaximander also reveals that Anaximander’s scientific approach is continuous with Hesiod’s mythological approach. Anaximander’s explanatory concerns closely resemble Hesiod’s, and the structure of Anaximander’s explanations imitates the structure of Hesiod’s. This is, perhaps, some reason for treating scientific inquiry as mythology matured rather than mythology abandoned.

https://classicalwisdom.com/people/philosophers/hesiod-and-anaximander-in-comparison/

No comments:

Post a Comment