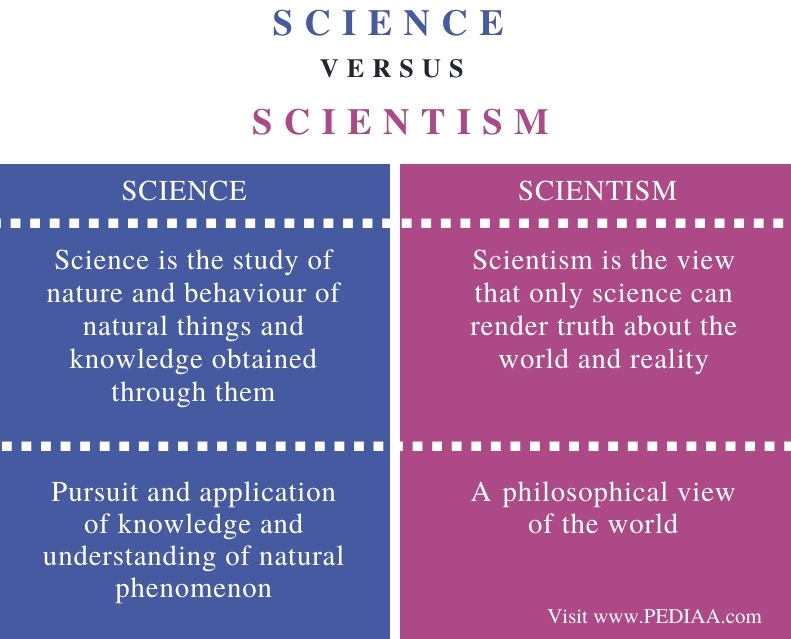

The main difference between science and scientism is that science is the study of nature and behaviour of natural things and knowledge obtained through them while scientism is the view that only science can render truth about the world and reality.

Science is the systematic and logical [study] of the structure and behaviour of the physical and natural world through observation and experiment. Although the term scientism is related to science, it has two basic meanings; it can refer to a philosophical view about the world as well as to the excessive or incorrect usage of science and scientific claims.

Key Areas Covered

1. What is Science

– Definition, Characteristics, Branches

2. What is Scientism

– Definition, Characteristics

3. What is the Difference Between Science and Scientism

– Comparison of Key Differences

Key Terms

Science, Scientism, Scientific Method

What is Science

Science is basically the study of nature and behaviour of natural things and knowledge obtained through them. It includes observation, identification, experimental investigation, description, and theoretical explanation of the natural phenomenon. The Science Council has defined science as below:

“Science is the pursuit and application of knowledge and understanding of the natural and social world following a systematic methodology based on evidence.”

The term science originates from the Latin word scientia, which means “knowledge”. Moreover, the earliest roots of science can be traced back to Ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia, around 3500 to 3000 BCE. Modern science, on the other hand, has three main categories as natural sciences, social sciences, and formal sciences. Moreover, disciplines that use existing scientific knowledge for practical applications are known as applied sciences. Subjects like engineering and medicine come under the field of applied science.

Branches of Science

Natural sciences involve the description, prediction, and understanding of natural phenomena according to empirical evidence from observation and experimentation. It has two main branches as life sciences (biological sciences) and physical sciences) It also includes sub-branches including chemistry, physics, earth sciences and astronomy. Social sciences, which studies society and the relationships among individuals within the society, includes many branches like anthropology, history, economics, archaeology, linguistics, political science. Formal science, on the other hand, is concerned with the study of formal systems and abstract concepts, and includes branches like mathematics, logic, and systems theory. However, some argue that formal sciences are not a part of science since they rely on deductive reasoning, instead of strictly relying on empirical evidence.

Furthermore, there are two types of scientific research as basic research and applied research: basic research involves the search for knowledge, whereas applied research involves the search for solutions to practical problems using this knowledge. When conducting scientific research, researchers use the scientific method to collect empirical evidence. This method involves systematic observation, measurement, and experiment, as well as the formulation, testing, and modification of hypotheses.

What is Scientism

Scientism is the view that science is the absolute and only justifiable access to the truth. According to this view, only science can render truth about the world and reality, and therefore, science should determine normative and epistemological values in society. Scientism is often a point of contention is philosophy. Moreover, it is often associated with logical positivism.

The term scientism also has a pejorative meaning. Sometimes, we use this word to refer to science applied in excess or improper usage of science or scientific claims.

Difference Between Science and Scientism

Definition

Science is the study of nature and behaviour of natural things and knowledge obtained through them. Scientism, on the other hand, is the view that only science can render truth about the world and reality.

Nature

Science is the pursuit and application of knowledge and understanding of natural phenomenon, whereas scientism is a philosophical view of the world.

Conclusion

The main difference between science and scientism is that science is the study of nature and behaviour of natural things and knowledge obtained through them while scientism is the view that only science can render truth about the world and reality.

Reference:

1. “Science.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 31 Oct. 2019, Available here.

2. “Scientism.” Wikipedia,

Wikimedia Foundation, 30 Sept. 2019, Available here.

3. “Our Definition of

Science.” The Science Council, Available here.

Image Courtesy:

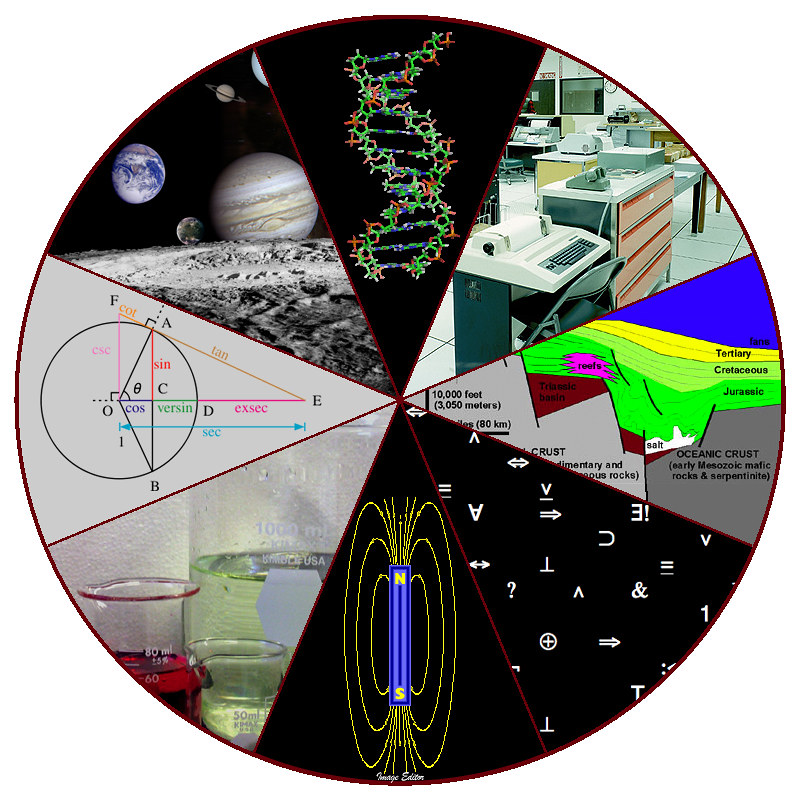

1. “Fields of Science” By Image Editor (CC BY 2.0) via Flickr

https://pediaa.com/what-is-the-difference-between-science-and-scientism/

A scientist, my dear friends, is a man who foresees; it is because science provides the means to predict that it is useful, and the scientists are superior to all other men. –Henri de Saint-Simon

Scientism is a rather strange word, but for reasons that we shall see, a useful one. Though this term has been coined rather recently, it is associated with many other “isms” with long and turbulent histories: materialism, naturalism, reductionism, empiricism, and positivism. Rather than tangle with each of these concepts separately, we’ll begin with a working definition of scientism and proceed from there.

Historian Richard G. Olson defines scientism as “efforts to extend scientific ideas, methods, practices, and attitudes to matters of human social and political concern.” (1) But this formulation is so broad as to render it virtually useless. Philosopher Tom Sorell offers a more precise definition: “Scientism is a matter of putting too high a value on natural science in comparison with other branches of learning or culture.” (2) MIT physicist Ian Hutchinson offers a closely related version, but more extreme: “Science, modeled on the natural sciences, is the only source of real knowledge.” (3) The latter two definitions are far more precise and will better help us evaluate scientism’s merit.

A History of Scientism

The Scientific Revolution

The roots of scientism extend as far back as early 17th century Europe, an era that came to be known as the Scientific Revolution. Up to that point, most scholars had been highly deferent to intellectual tradition, largely a combination of Judeo-Christian scripture and ancient Greek philosophy. But a torrent of new learning during the late Renaissance began to challenge the authority of the ancients, and long-established intellectual foundations began to crack. The Englishman Francis Bacon, the Frenchman Rene Descartes, and the Italian Galileo Galilei spearheaded an international movement proclaiming a new foundation for learning, one that involved careful scrutiny of nature instead of analysis of ancient texts.

Descartes and Bacon used particularly strong rhetoric to carve out space for their new methods. They claimed that by learning how the physical world worked, we could become “masters and possessors of nature.”(4) In doing so, humans could overcome hunger through innovations in agriculture, eliminate disease through medical research, and dramatically improve overall quality of life through technology and industry. Ultimately, science would save humans from unnecessary suffering and their self-destructive tendencies. And it promised to achieve these goals in this world, not the afterlife. It was a bold, prophetic vision.

As this new method found great success, the specter of scientism began to emerge. Both Bacon and Descartes elevated the use of reason and logic by denigrating other human faculties such as creativity, memory, and imagination. Bacon’s classification of learning demoted poetry and history to second-class status. (5) Descartes’ rendering of the entire universe as a giant machine left little room for the arts or other forms of human expression. In one sense, the rhetoric of these visionaries opened great new vistas for intellectual inquiry. But on the other hand, it proposed a vastly narrower range of which human activities were considered worthwhile.

The Enlightenment

A century later, many of the Enlightenment intellectuals continued their love-affair with the power of natural science. They claimed that not only could science enhance the quality of human life, it could even promote moral improvement. The Encyclopedist Denis Diderot aimed to collect, organize, and preserve all human knowledge so that “our children, becoming better instructed, may become at the same time more virtuous and happy.” (6) Many of the French philosophes even claimed that science could be a substitute for religion. In fact, during the French Revolution, numerous Catholic churches were converted into “Temples of Reason” and held quasi-religious services for the worship of science. (7)

Positivism

The 19th century witnessed the most powerful and enduring formulation of scientism, a system called positivism. Its founder was August Comte, who built his positive philosophy from a deep commitment to David Hume’s empiricism and skepticism. Comte claimed that the only valid data is acquired through the senses. Nothing was transcendent, and nothing metaphysical could have any claim to validity (8). The task of scientists was twofold—first, to demonstrate how all phenomena, including human behavior, are subject to invariable natural laws (9). Second, they would reduce these natural laws to the smallest possible number, and ultimately unify them under the laws of physics (10).

Comte also had a clear sense of the trajectory of intellectual history, which he called The Law of Three Stages: Each branch of knowledge passes through three stages: the theological or fictitious, the metaphysical or abstract, and lastly the scientific or positive state. He believed that through the continual advancement of human understanding, religion would fade away, philosophy and the humanities would be transformed into a naturalistic basis, and all human knowledge would eventually become a product of science. Any ideas outside that realm would be pure fantasy or superstition.

Logical Positivism

Positivism did not lose its appeal in the 20th century. To the contrary, a group known collectively as The Vienna Circle reinvigorated the fundamental tenets of positivism with enhanced symbolic logic and semantic theory. They called their approach, fittingly, logical positivism. In this system, there are only two kinds of meaningful statements: analytic statements (including logic and mathematics), and empirical statements, subject to experimental verification. Anything outside of this framework is an empty concept. (11)

Given its sweeping claims, logical positivism came under heavy scrutiny. Karl Popper pointed out that few statements in science can actually be completely verified. However, a single observation has the potential to invalidate a hypothesis, and even an entire theory. Therefore, he proposed that instead of experimental verification, the principle of falsifiability should demarcate what qualified as science, and by extension, what can qualify as knowledge. (add footnote here and renumber)

Another weakness of the positivist position is its reliance on a complete distinction between theory and observation. Observations, essential to the empirical approach of science, were claimed by positivists to be brute facts which one could use to establish, evaluate, and compare the theories. However, W.O. Quine pointed out in his “Two Dogmas of Empiricism” that observations themselves are partly shaped by theory (“theory-laden”). (12) What counts as an observation, how to construct an experiment, and what data you think your instruments are collecting—all require an interpretive theoretical framework. This realization does not deal a death-blow to the practice of science (as some post-modernists like to claim), but it does undermine the positivist claim that science rests entirely on facts, and is thus an indisputable foundation for knowledge.

Scientism of Today

Scientism today is alive and well, as evidenced by the statements of our celebrity scientists:

“The Cosmos is all that is or ever was or ever will be.” –Carl Sagan, Cosmos

“The more the universe seems comprehensible, the more it also seems pointless.” –Stephen Weinburg, The First Three Minutes

“We can be proud as a species because, having discovered that we are alone, we owe the gods very little.” –E.O. Wilson, Consilience

While these men are certainly entitled to their personal opinions and the freedom to express them, the fact that they make such bold claims in their popular science literature blurs the line between solid, evidence-based science, and rampant philosophical speculation. Whether one agrees with the sentiments of these scientists or not, the result of these public pronouncements has served to alienate a large segment of American society. And that is a serious problem, since scientific research relies heavily upon public support for its funding, and environmental policy is shaped by lawmakers who listen to their constituents. From a purely pragmatic standpoint, it would be wise to try a different approach.

Physicist Ian Hutchinson offers an insightful metaphor for the current controversies over science:

“The health of science is in fact jeopardized by scientism, not promoted by it. At the very least, scientism provokes a defensive, immunological, aggressive response from other intellectual communities, in return for its own arrogance and intellectual bullyism. It taints science itself by association.” (13)

Noting that most Americans enthusiastically welcome scientific advancements, particularly those in health care, transportation, and communications, Hutchinson suggests that perhaps what the public is rejecting is not actually science itself, but a worldview that closely aligns itself with science—scientism (14). By disentangling these two concepts, we have a much better chance for enlisting public support for scientific research than we would by trying to convince millions of people to embrace a materialistic, godless universe in which science is our only remaining hope.

Distinguishing Science from Scientism

So if science is distinct from scientism, what is it? Science is an activity that seeks to explore the natural world using well-established, clearly-delineated methods. Given the complexity of the universe, from the very big to very small, from inorganic to organic, there is a vast array of scientific disciplines, each with its own specific techniques. The number of different specializations is constantly increasing, leading to more questions and areas of exploration than ever before. Science expands our understanding, rather than limiting it.

Scientism, on the other hand, is a speculative worldview about the ultimate reality of the universe and its meaning. Despite the fact that there are millions of species on our planet, scientism focuses an inordinate amount of its attention on human behavior and beliefs. Rather than working within carefully constructed boundaries and methodologies established by researchers, it broadly generalizes entire fields of academic expertise and dismisses many of them as inferior. With scientism, you will regularly hear explanations that rely on words like “merely”, “only”, “simply”, or “nothing more than”. Scientism restricts human inquiry.

It is one thing to celebrate science for its achievements and remarkable ability to explain a wide variety of phenomena in the natural world. But to claim there is nothing knowable outside the scope of science would be similar to a successful fisherman saying that whatever he can’t catch in his nets does not exist (15). Once you accept that science is the only source of human knowledge, you have adopted a philosophical position (scientism) that cannot be verified, or falsified, by science itself. It is, in a word, unscientific.

Thomas Burnett is the assistant director of public engagement at the John Templeton Foundation. As a science writer, Thomas has also worked for The National Academy of Sciences and the American Association for the Advancement of Science. He has degrees in philosophy and the history of science from Rice University and University of California, Berkeley.

NOTES

1. Olson, Richard G. Science and Scientism in Nineteenth-Century Europe. Urbana, University of Illinois Press, 2008.

2. Sorell, Tom. Scientism: Philosophy and the Infatuation with Science. New York: Routledge, 1991.

3. Hutchinson, Ian. Monopolizing Knowledge: A Scientist Refutes Religion-Denying, Reason-Destroying Scientism. Belmont, MA: Fias Publishing, 2011.

4. Descartes, Rene. Discourse on Method

5. Sorell, p176

6. Sorell, p35

7. Ozouf, Mona (1988). Festivals and the French Revolution. Harvard University Press

8. Zammito, John H. A Nice Derangement of Epistemes : Post-Positivism in the Study of Science from Quine to Latour. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2004.

9. This view is a form of strict determinism, and current popularizers of continue to enthusiastically endorse it. Perhaps they are “determined” to do so?

10. This view is a form of extreme reductionism, also widely endorsed by current popularizers of science.

11. Zammito, p8

12. Popper, Karl. Logic of Scientific Discovery. 1959)

13. For an extended discussion, read Zammito’s chapter “The Perils of Semantic Ascent: Quine and Post-positivism in the Philosophy of Science” in A Nice Derangement of Epistemes

14. Hutchinson, p143

15. Hutchinson, p109

16. Giberson, Karl, and Mariano Artigas. Oracles of Science: Celebrity Scientists Versus God and Religion. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009.

https://www.aaas.org/programs/dialogue-science-ethics-and-religion/what-scientism

Image of man — the ‘scientific’ versus ‘manifest’ images of Wilfrid Sellars

David Misselbrook

We are exhorted to make our medicine rigorously evidence based and yet robustly patient centred. We find ourselves having to square a circle. Why is it that these two aspects of medicine seem so determined to pull apart? And why is it that the scientific picture of evidence-based medicine always gets to play front of stage?

The US Philosopher Wilfrid Sellars describes two images or pictures of man. The scientific image of man is familiar to medics; it’s all about body tissues, genes, and biochemistry. But what if science is not the only valid way of knowing? Sellars sees the ‘manifest image’ of man as ‘the framework in terms of which, to use an existentialist turn of phrase, man first encountered himself’. The manifest image is connected to personhood and self-awareness, it is how I think of myself every day. Pascal said, ‘Man is but a reed, the most feeble thing in nature; but he is a thinking reed … But, if the universe were to crush him, man would still be more noble than that which killed him, because he knows that he dies and the advantage which the universe has over him; the universe knows nothing of this’.Consciousness, although contingent and frail, is qualitatively unique and is of great value.

Scientific knowledge is not the only sort of knowledge that is important to persons. ‘I love my wife’ is an important piece of knowledge to me, but it cannot be derived scientifically. It is an example of what is sometimes called ‘personalistic knowledge’.

Frank Jackson formally demonstrates the validity of such personalistic knowledge. If physical science can tell us all that can be known then a colourblind person must be able to know what it is to see red. We can construct this knowledge scientifically around a model of having the right sort of cones in the retina to perceive incident light with a wavelength of 650 nm. Yet if this person, in possession of all available knowledge about redness, were to be cured of their colour blindness then they will learn something new that they did not know before, what it is to see red. Jackson’s argument is a demonstration of something both profound and also obvious to all but the most extreme physicalist. What it is to be me cannot be contained within a scientific account of the self.

Sure, we could join a narrow band of neuroscientists and say that our consciousness is a cognitive delusion. The belief that the methods of natural science are valid in all fields of human enquiry is called ‘Scientism’. Scientism seems touchingly modernistic, and reminiscent of other imperialist systems such as Communism, or Hegel’s belief that in fact it is philosophy that defines and encompasses all truth.

Sellars claims that the scientific image of man is not able to encompass or comprehend the manifest image but that both are equally valid ways of knowing about man. As humans, personalistic knowledge is our fundamental concern. If science showed that in fact E = MC3 I would be surprised but not fundamentally disturbed. But mess with my personalistic knowledge and that affects me deeply.

No comments:

Post a Comment